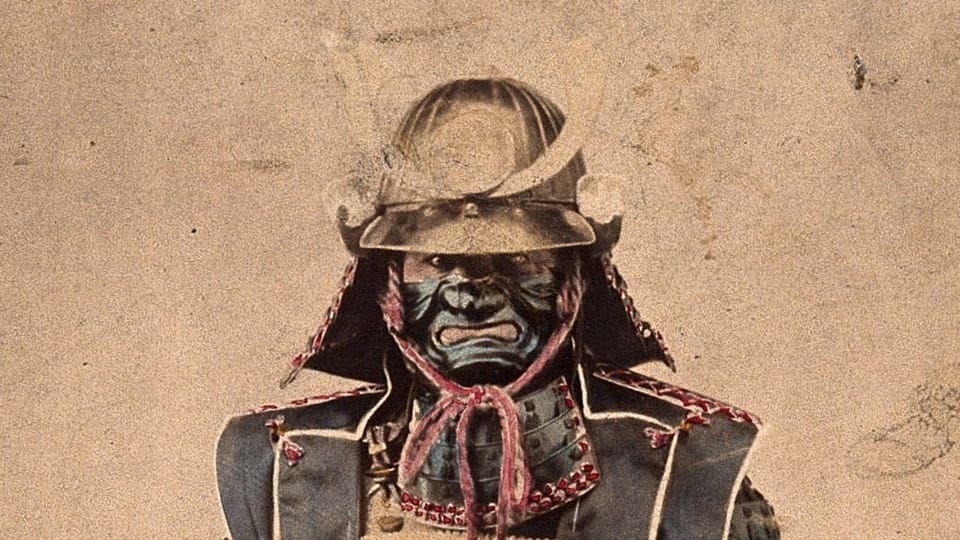

Bushidō: The Samurai Code that Shaped Japan’s History and Identity

Bushidō is the code of conduct of the samurai class in old-school Japan. It evolved over centuries, ending up as a set of values all about honor, loyalty, and obedience. This code wasn’t just for the samurai, it became the backbone of Japan’s ethical training in the mid-19th century. And you know what? It fueled Japanese nationalism, gave them a sense of pride, especially during the wars.

But get this: even after Japan got knocked out in World War II, pieces of Bushidō still stuck around. You can find it in Japanese martial arts and their cultural practices.

Get beyond love and grief: exist for the good of Man. —Miyamoto Musashi

Let’s back it up to the Kamakura period, between 1192 and 1333. That’s when Bushidō started taking shape, along with the practice of seppuku, basically ritual disembowelment. You got these samurai, right, and they’re the embodiment of martial spirit and loyalty, all under the rule of the shogun. These guys lived by Bushidō, which meant being top-notch warriors, showing fearlessness in battle, living frugally, being kind, honest, and honorable. But above all, loyalty to their lord.

Fast forward to the Edo period, 1603 to 1867, and Bushidō gets an upgrade. It’s infused with Confucian ethics, pushing the idea of duty and obedience to authority even harder. Take the story of the 47 rōnin, for instance. These guys avenged their lord’s death and then committed ritual suicide as ordered. That’s some serious dedication right there.

Off the battlefield, it was all about honor, self-control, and being a decent human being. No room for letting your emotions cloud your judgment.

Come the 20th century, and Bushidō becomes a tool for promoting Japanese nationalism. It even motivated Japanese pilots during World War II. Talk about dedication, huh?

Now, about Chiune Sugihara, a man with Bushidō running in his veins. His mom came from a long line of samurai, so you’d think he'd be all about that code, right? Well, kinda. See, Sugihara did some pretty noble stuff, like issuing unauthorized visas to Jewish refugees in Lithuania in 1940. That’s straight-up Bushidō, the noble altruism and all. But here’s the kicker: Sugihara had this streak of individualism. He defied his old man’s wish for him to study medicine, and he went against the government to issue those visas. Plus, he converted to Christianity as an adult. So maybe, just maybe, Bushidō wasn’t his main thing after all.