Akutō and Rural Conflict in Medieval Japan

I hate Facebook as much as the next guy. It’s a dumpster fire of misinformation and clickbait. But...and here’s the kicker...I can’t deny it’s got its uses. Especially when it comes to niche groups like the Historical Ninjutsu and Samurai Warfare forum. Founded by none other than Antony Cummins—a guy who knows his stuff when it comes to feudal Japan (check out my Q&A with the man here)—it’s where the real heavy hitters of academic discussion on samurai-era combat come to throw down. It’s like the nerdy fight club of history.

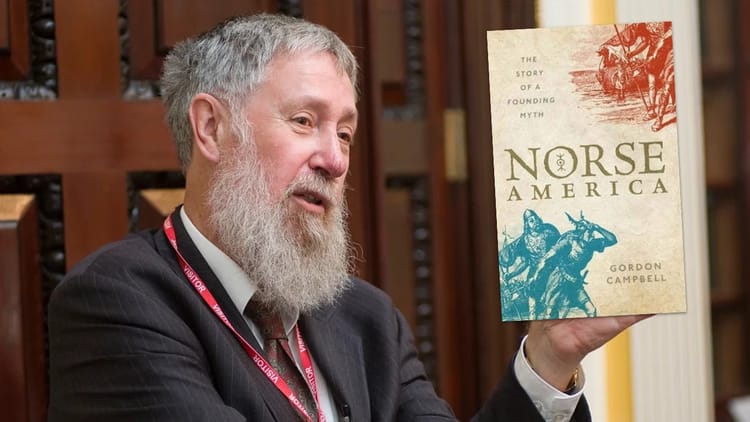

So get this, a few months back, I threw out a question, like casting a line into the void: “Hey, what’s out there on samurai strategy besides The Five Rings by Miyamoto Musashi?” And boom, Nico Vázquez Arrieta—quick as lightning—recommends Akutō and Rural Conflict in Medieval Japan by Morten Oxenboell. Let me tell you, this book blew my mind. I ate it up, front to back, and it sparked the hell outta the latest issue of VIKINGS vs SAMURAI. That’s right, you’re gonna see more of those medieval ‘evil bands’—the akutō—showing up in my stories from here on out. Strap in.

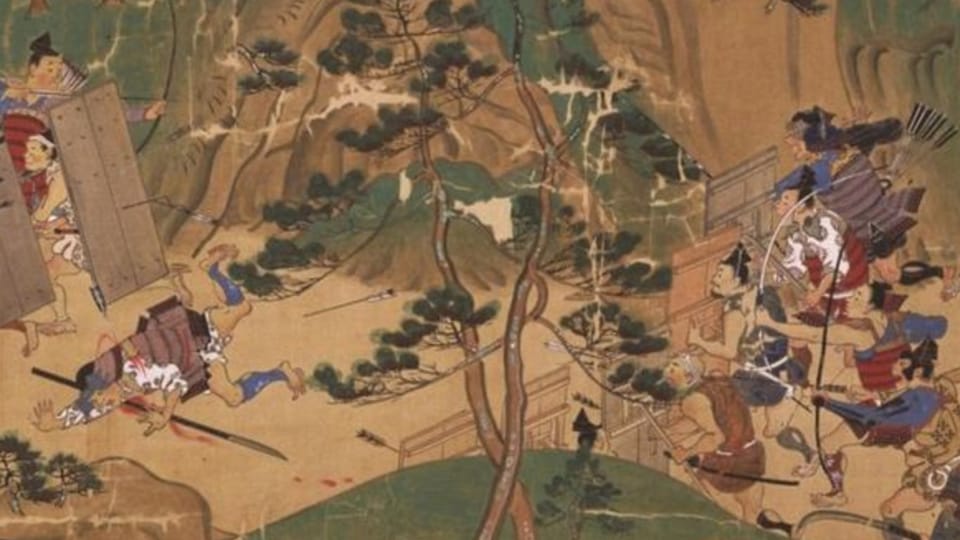

Now, Oxenboell’s Akutō digs into this side of Japanese history most people wouldn’t even think twice about. It’s the kind of history that hits you in the gut. These akutō? They were labeled as “evil bands,” but Oxenboell pulls back the curtain to show how they were more than just chaos-inciting bandits. They were playing the game, navigating the feudal mess that was 13th and 14th century Japan. The Kamakura regime, the imperial court, absentee landlords—everyone was clawing for power. And these rural communities? They were smack dab in the middle, using violence not for kicks, but to negotiate rights and survival. It's not just about swinging swords—it’s about who gets to swing ‘em and why.

Oxenboell flips the script here, challenging this lazy notion that these groups were just troublemakers. No, man, this was chess with bloodshed. And by focusing on the local perspective instead of the lords and samurai elites, Oxenboell paints a world where the rural folks weren’t just sitting ducks. They fought back, they strategized, they built these delicate, tension-filled relationships with absentee landlords. And what makes it brilliant is that this wasn’t chaos for the sake of chaos. These “evil bands” were part of a fragile system of checks and balances, maintaining order in a world that was far from simple.

Now, here’s why this book hit home for me—because my saga, VIKINGS vs SAMURAI, takes place right in the Kamakura period. Japan’s going through this transformation, the Mongols are knockin’ at the door, and in my version of events? Yeah, the Vikings are kicking that door down instead. But here’s the thing, the conflicts and power struggles Oxenboell lays out—the fights over land, the legal battles—it’s all there. I soaked it up like a sponge. And it’s gonna bleed into my storytelling. Vikings, samurai, and akutō—oh yeah, it’s all coming together.

I learned from this book that by the mid-1200s, the Kamakura warrior government wasn’t just handling military affairs. They were running the courts, managing administration, and propping up their own authority with the prestige of the imperial court. This was no simple system. It was a battlefield of bureaucracy and violence. Akutō weren’t just popping up out of nowhere. They were the result of absentee landlords losing their grip, local managers screwing things up, and the villagers saying, “Enough is enough.” The shogunate and the court got involved, but not because they cared about peace. They cared about keeping their power. And that’s where the term akutō comes in—a weaponized label, a smear tactic used in courtrooms to paint people as villains.

Hell, you even see this in the conflict between Tametoki and the Kōya monks—where calling someone akutō wasn’t just name-calling, it was a death sentence. By the time you hit the Nanboku-chō period, the term akutō starts to disappear, but not because these guys vanished. Nah, they just got absorbed into bigger war bands. The chaos wasn’t chaos—it was the evolution of power dynamics.

By the time I finished the book, I realized just how much this messy, violent, but deeply strategic society inspired my work. Medieval Japan wasn’t some neat and tidy war zone—it was a boiling pot of conflict and negotiation. And that’s what’s so damn compelling about this history. It wasn’t about breakdown—it was about survival. Everyone was a player, from the landlords to the peasants to the guys wielding the swords.

So yeah, you bet your ass the spirit of the akutō is gonna live on in VIKINGS vs SAMURAI. They’re gonna be rebels, sure—but not just rebels. They’ll be symbols of a society constantly struggling, constantly fighting for autonomy, for survival. And when they rise, challenging authority, cutting deals, and fighting like hell, they’ll carry the weight of history with them.